Valentine’s Day | Love Day’s History

ویلنٹائن ڈے کی حقیقت، اسکی تاریخی اہمیت اور اسکا شرعی حکم؛ تمام اردو مضامین کیلئے اردو سکائی ڈاٹ کام پر دوبارہ وزٹ کریں 14 فروری 2011 کو

Saint Valentine’s Day, commonly shortened to Valentine’s Day,[1][2][3] is an annual commemoration held on February 14 celebrating love and affection between intimate companions.[1][3] The day is named after one or more early Christian martyrs, Saint Valentine, and was established by Pope Gelasius I in 500 AD. It was deleted from the Roman calendar of saints in 1969 by Pope Paul VI, but its religious observance is still permitted. It is traditionally a day on which lovers express their love for each other by presenting flowers, offering  confectionery, and sending greeting cards (known as “valentines“). The day first became associated with romantic love in the circle of Geoffrey Chaucer in the High Middle Ages, when the tradition of courtly love flourished.

confectionery, and sending greeting cards (known as “valentines“). The day first became associated with romantic love in the circle of Geoffrey Chaucer in the High Middle Ages, when the tradition of courtly love flourished.

Modern Valentine’s Day symbols include the heart-shaped outline, doves, and the figure of the winged Cupid. Since the 19th century, handwritten valentines have given way to mass-produced greeting cards.[4]

Historical facts

Numerous early Christian martyrs were named Valentine.[5] The Valentines honored on February 14 are Valentine of Rome (Valentinus presb. m. Romae) and Valentine of Terni (Valentinus ep. Interamnensis m. Romae).[6] Valentine of Rome[7] was a priest in Rome who was martyred about AD 269 and was buried on the Via Flaminia. His relics are at the Church of Saint Praxed in Rome,[8] and at Whitefriar Street Carmelite Church in Dublin, Ireland.

Valentine of Terni[9] became bishop of Interamna (modern Terni) about AD 197 and is said to have been martyred during the persecution under Emperor Aurelian. He is also buried on the Via Flaminia, but in a different location than Valentine of Rome. His relics are at the Basilica of Saint Valentine in Terni (Basilica di San Valentino).[10]

The Catholic Encyclopedia also speaks of a third saint named Valentine who was mentioned in early martyrologies under date of February 14. He was martyred in Africa with a number of companions, but nothing more is known about him.[11]

No romantic elements are present in the original early medieval biographies of either of these martyrs. By the time a Saint Valentine became linked to romance in the 14th century, distinctions between Valentine of Rome and Valentine of Terni were utterly lost.[12]

In the 1969 revision of the Roman Catholic Calendar of Saints, the feastday of Saint Valentine on February 14 was removed from the General Roman Calendar and relegated to particular (local or even national) calendars for the following reason: “Though the memorial of Saint Valentine is ancient, it is left to particular calendars, since, apart from his name, nothing is known of Saint Valentine except that he was buried on the Via Flaminia on February 14.”[13] The feast day is still celebrated in Balzan (Malta) where relics of the saint are claimed to be found, and also throughout the world by Traditionalist Catholics who follow the older, pre-Second Vatican Council calendar.

Romantic legends

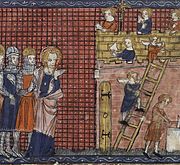

Saint Valentine of Terni and his disciples.

The Early Medieval acta of either Saint Valentine were expounded briefly in Legenda Aurea.[14] According to that version, St Valentine was persecuted as a Christian and interrogated by Roman Emperor Claudius II in person. Claudius was impressed by Valentine and had a discussion with him, attempting to get him to convert to Roman paganism in order to save his life. Valentine refused and tried to convert Claudius to Christianity instead. Because of this, he was executed. Before his execution, he is reported to have performed a miracle by healing the blind daughter of his jailer.

Since Legenda Aurea still provided no connections whatsoever with sentimental love, appropriate lore has been embroidered in modern times to portray Valentine as a priest who refused an unattested law attributed to Roman Emperor Claudius II, allegedly ordering that young men remain single. The Emperor supposedly did this to grow his army, believing that married men did not make for good soldiers. The priest Valentine, however, secretly performed marriage ceremonies for young men. When Claudius found out about this, he had Valentine arrested and thrown in jail.

There is an additional modern embellishment to The Golden Legend, provided by American Greetings to History.com, and widely repeated despite having no historical basis whatsoever. On the evening before Valentine was to be executed, he would have written the first “valentine” card himself, addressed to a young girl variously identified as his beloved,[15] as the jailer’s daughter whom he had befriended and healed,[16] or both. It was a note that read “From your Valentine.”[15]

Attested traditions

Lupercalia

Though popular modern sources link unspecified Greco-Roman February holidays alleged to be devoted to fertility and love to St. Valentine’s Day, Professor Jack Oruch of the University of Kansas argued that prior to Chaucer, no links between the Saints named Valentinus and romantic love existed.[17] Earlier links as described above were focused on sacrifice rather than romantic love. In the ancient Athenian calendar the period between mid-January and mid-February was the month of Gamelion, dedicated to the sacred marriage of Zeus and Hera.

In Ancient Rome, Lupercalia, observed February 13 through 15, was an archaic rite connected to fertility. Lupercalia was a festival local to the city of Rome. The more general Festival of Juno Februa, meaning “Juno the purifier “or “the chaste Juno,” was celebrated on February 13–14. Pope Gelasius I (492–496) abolished Lupercalia.

Geoffrey Chaucer by Thomas Occleve (1412)

Chaucer’s love birds

The first recorded association of Valentine’s Day with romantic love is in Parlement of Foules (1382) by Geoffrey Chaucer[18] Chaucer wrote:

For this was on seynt Volantynys day

Whan euery bryd comyth there to chese his make.

[“For this was Saint Valentine’s Day, when every bird cometh there to choose his mate.”]

This poem was written to honor the first anniversary of the engagement of King Richard II of England to Anne of Bohemia.[19] A treaty providing for a marriage was signed on May 2, 1381.[20] (When they were married eight months later, they were each only 15 years old).

Readers have uncritically assumed that Chaucer was referring to February 14 as Valentine’s Day; however, mid-February is an unlikely time for birds to be mating in England. Henry Ansgar Kelly has pointed out[21] that in the liturgical calendar, May 2 is the saints’ day for Valentine of Genoa. This St. Valentine was an early bishop of Genoa who died around AD 307.[22]

Chaucer’s Parliament of Foules is set in a fictional context of an old tradition, but in fact there was no such tradition before Chaucer. The speculative explanation of sentimental customs, posing as historical fact, had their origins among 18th-century antiquaries, notably Alban Butler, the author of Butler’s Lives of Saints, and have been perpetuated even by respectable modern scholars. Most notably, “the idea that Valentine’s Day customs perpetuated those of the Roman Lupercalia has been accepted uncritically and repeated, in various forms, up to the present”[23]

Medieval period and the English Renaissance

Using the language of the law courts for the rituals of courtly love, a “High Court of Love” was established in Paris on Valentine’s Day in 1400. The court dealt with love contracts, betrayals, and violence against women. Judges were selected by women on the basis of a poetry reading.[24][25] The earliest surviving valentine is a 15th-century rondeau written by Charles, Duke of Orleans to his wife, which commences.

Je suis desja d’amour tanné

Ma tres doulce Valentinée…—Charles d’Orléans, Rondeau VI, lines 1–2 [26]

At the time, the duke was being held in the Tower of London following his capture at the Battle of Agincourt, 1415.[27]

Valentine’s Day is mentioned ruefully by Ophelia in Hamlet (1600–1601):

To-morrow is Saint Valentine’s day,

All in the morning betime,

And I a maid at your window,

To be your Valentine.

Then up he rose, and donn’d his clothes,

And dupp’d the chamber-door;

Let in the maid, that out a maid

Never departed more.—William Shakespeare, Hamlet, Act IV, Scene 5

John Donne used the legend of the marriage of the birds as the starting point for his Epithalamion celebrating the marriage of Elizabeth, daughter of James I of England, and Frederick V, Elector Palatine on Valentine’s Day:

Hayle Bishop Valentine whose day this is

All the Ayre is thy Diocese

And all the chirping Queristers

And other birds ar thy parishioners

Thou marryest every yeare

The Lyrick Lark, and the graue whispering Doue,

The Sparrow that neglects his life for loue,

The houshold bird with the redd stomacher

Thou makst the Blackbird speede as soone,

As doth the Goldfinch, or the Halcyon

The Husband Cock lookes out and soone is spedd

And meets his wife, which brings her feather-bed.

This day more cheerfully than ever shine

This day which might inflame thy selfe old Valentine.—John Donne, Epithalamion Vpon Frederick Count Palatine and the Lady Elizabeth marryed on St. Valentines day

The verse Roses are red echoes conventions traceable as far back as Edmund Spenser‘s epic The Faerie Queene (1590):

She bath’d with roses red, and violets blew,

And all the sweetest flowres, that in the forrest grew.[28]

The modern cliché Valentine’s Day poem can be found in the collection of English nursery rhymes Gammer Gurton’s Garland (1784):

The rose is red, the violet’s blue

The honey’s sweet, and so are you

Thou are my love and I am thine

I drew thee to my Valentine

The lot was cast and then I drew

And Fortune said it shou’d be you.[29]

Modern times

In 1797, a British publisher issued The Young Man’s Valentine Writer, which contained scores of suggested sentimental verses for the young lover unable to compose his own. Printers had already begun producing a limited number of cards with verses and sketches, called “mechanical valentines,” and a reduction in postal rates in the next century ushered in the less personal but easier practice of mailing Valentines. That, in turn, made it possible for the first time to exchange cards anonymously, which is taken as the reason for the sudden appearance of racy verse in an era otherwise prudishly Victorian.[30]

Paper Valentines became so popular in England in the early 19th century that they were assembled in factories. Fancy Valentines were made with real lace and ribbons, with paper lace introduced in the mid-19th century.[31] In the UK, just under half the population spend money on their Valentines and around 1.3 billion pounds is spent yearly on cards, flowers, chocolates and other gifts, with an estimated 25 million cards being sent.[32] The reinvention of Saint Valentine’s Day in the 1840s has been traced by Leigh Eric Schmidt.[33] As a writer in Graham’s American Monthly observed in 1849, “Saint Valentine’s Day… is becoming, nay it has become, a national holyday.”[34] In the United States, the first mass-produced valentines of embossed paper lace were produced and sold shortly after 1847 by Esther Howland (1828–1904) of Worcester, Massachusetts.[35][36]

Her father operated a large book and stationery store, but Howland took her inspiration from an English Valentine she had received from a business associate of her father.[37][38] Intrigued with the idea of making similar Valentines, Howland began her business by importing paper lace and floral decorations from England.[38][39] The English practice of sending Valentine’s cards was established enough to feature as a plot device in Elizabeth Gaskell‘s Mr. Harrison’s Confessions (1851): “I burst in with my explanations: ‘”The valentine I know nothing about.” ‘”It is in your handwriting,” said he coldly.[40] Since 2001, the Greeting Card Association has been giving an annual “Esther Howland Award for a Greeting Card Visionary.”[36]

Since the 19th century, handwritten notes have given way to mass-produced greeting cards.[4] The mid-19th century Valentine’s Day trade was a harbinger of further commercialized holidays in the United States to follow.[41]

In the second half of the 20th century, the practice of exchanging cards was extended to all manner of gifts in the United States. Such gifts typically include roses and chocolates packed in a red satin, heart-shaped box. In the 1980s, the diamond industry began to promote Valentine’s Day as an occasion for giving jewelry.

The U.S. Greeting Card Association estimates that approximately 190 million valentines are sent each year in the US. Half of those valentines are given to family members other than husband or wife, usually to children. When you include the valentine-exchange cards made in school activities the figure goes up to 1 billion, and teachers become the people receiving the most valentines.[35] In some North American elementary schools, children decorate classrooms, exchange cards, and are given sweets. The greeting cards of these students sometimes mention what they appreciate about each other.

The rise of Internet popularity at the turn of the millennium is creating new traditions. Millions of people use, every year, digital means of creating and sending Valentine’s Day greeting messages such as e-cards, love coupons or printable greeting cards. An estimated 15 million e-valentines were sent in 2010.[35]

Antique and vintage Valentines, 1850–1950

Valentines of the mid-19th and early 20th centuries

|

Valentine card, 1862: “My dearest Miss, I send thee a kiss” addressed to Miss Jenny Lane of Crostwight Hall, Smallburgh, Norfolk. |

|||

Postcards, “pop-ups”, and mechanical Valentines, circa 1900–1930

|

Advertisement for Prang’s greeting cards, 1883 |

|||

Children’s Valentines

Similar days honoring love

In the West

Europe

| Part of a series on love |

| Basic aspects |

|---|

| Charity |

| Human bonding |

| Chemical basis |

While sending cards, flowers, chocolates and other gifts is traditional in the UK, Valentine’s Day has various regional customs. In Norfolk, a character called ‘Jack’ Valentine knocks on the rear door of houses leaving sweets and presents for children. Although he was leaving treats, many children were scared of this mystical person. In Wales, many people celebrate Dydd Santes Dwynwen (St Dwynwen’s Day) on January 25 instead of (or as well as) Valentine’s Day. The day commemorates St Dwynwen, the patron saint of Welsh lovers. In France, a traditionally Catholic country, Valentine’s Day is known simply as “Saint Valentin“, and is celebrated in much the same way as other western countries. In Spain Valentine’s Day is known as “San Valentín” and is celebrated the same way as in the UK, although in Catalonia it is largely superseded by similar festivities of rose and/or book giving on La Diada de Sant Jordi (Saint George’s Day). In Portugal it is more commonly referred to as “Dia dos Namorados” (Lover’s Day / Day of those that are in love with each other).

In Denmark and Norway, Valentine’s Day (14 Feb) is known as Valentinsdag. It is not celebrated to a large extent, but is largely imported from American culture, and some people take time to eat a romantic dinner with their partner, to send a card to a secret love or give a red rose to their loved one. The flower industry in particular is still working on promoting the holiday. In Sweden it is called Alla hjärtans dag (“All Hearts’ Day”) and was launched in the 1960s by the flower industry’s commercial interests, and due to the influence of American culture. It is not an official holiday, but its celebration is recognized and sales of cosmetics and flowers for this holiday are only exceeded by those for Mother’s Day.

In Finland Valentine’s Day is called Ystävänpäivä which translates into “Friend’s day”. As the name indicates, this day is more about remembering all your friends, not only your loved ones. In Estonia Valentine’s Day is called Sõbrapäev, which has the same meaning.

In Slovenia, a proverb says that “St Valentine brings the keys of roots,” so on February 14, plants and flowers start to grow. Valentine’s Day has been celebrated as the day when the first work in the vineyards and in the fields commences. It is also said that birds propose to each other or marry on that day. Nevertheless, it has only recently been celebrated as the day of love. The day of love is traditionally March 12, the Saint Gregory‘s day. Another proverb says “Valentin – prvi spomladin” (“Valentine — first saint of spring”), as in some places (especially White Carniola) Saint Valentine marks the beginning of spring.

In Romania, the traditional holiday for lovers is Dragobete, which is celebrated on February 24. It is named after a character from Romanian folklore who was supposed to be the son of Baba Dochia. Part of his name is the word drag (“dear”), which can also be found in the word dragoste (“love”). In recent years, Romania has also started celebrating Valentine’s Day, despite already having Dragobete as a traditional holiday. This has drawn backlash from many groups, reputable persons and institutions[42] but also nationalist organizations like Noua Dreaptǎ, who condemn Valentine’s Day for being superficial, commercialist and imported Western kitsch.

Valentine’s Day is called Sevgililer Günü in Turkey, which translates into “Sweethearts’ Day”.

According to Jewish tradition the 15th day of the month of Av – Tu B’Av (usually late August) is the festival of love. In ancient times girls would wear white dresses and dance in the vineyards, where the boys would be waiting for them (Mishna Taanith end of Chapter 4). In modern Israeli culture this is a popular day to pronounce love, propose marriage and give gifts like cards or flowers.

Mexico, Central and South America

In some Latin American countries Valentine’s Day is known as “Día del Amor y la Amistad” (Day of Love and Friendship). For example Mexico,[43] Costa Rica,[44] and Ecuador,[45] as well others. Although it is similar to the United States’ version in many ways, it is also common to see people do “acts of appreciation” for their friends.

In Guatemala it is known as the “Día del Cariño” (Day of the Affection).[46]

In Brazil, the Dia dos Namorados (lit. “Day of the Enamored”, or “Boyfriends’/Girlfriends’ Day”) is celebrated on June 12, when couples exchange gifts, chocolates, cards and flower bouquets. This day was chosen probably because it is the day before the Festa junina (Saint Anthony’s day), known there as the marriage saint, when traditionally many single women perform popular rituals, called simpatias, in order to find a good husband or boyfriend. The February 14’s Valentine’s Day is not celebrated at all, mainly for cultural and commercial reasons, since it usually falls too little before or after Carnival, a major floating holiday in Brazil — long regarded as a holiday of sex and debauchery by many in the country[47] — that can fall anywhere from early February to early March.

In Venezuela, in 2009, President Hugo Chávez said in a meeting to his supporters for the upcoming referendum vote on February 15, that “since on the 14th, there will be no time of doing nothing, nothing or next to nothing … maybe a little kiss or something very superficial”, he recommended people to celebrate a week of love after the referendum vote.[48]

In most of South America the Día del amor y la amistad and the Amigo secreto (“Secret friend”) are quite popular and usually celebrated together on the 14 of February (one exception is Colombia, where it is celebrated every third Saturday of September). The latter consists of randomly assigning to each participant a recipient who is to be given an anonymous gift (similar to the Christmas tradition of Secret Santa).

Asia

Thanks to a concentrated marketing effort, Valentine’s Day is celebrated in some Asian countries with Singaporeans, Chinese and South Koreans spending the most money on Valentine’s gifts.[49]

In South Korea, similar to Japan, women give chocolate to men on February 14, and men give non-chocolate candy to women on March 14 (White Day). On April 14 (Black Day), those who did not receive anything on the 14th of Feb or March go to a Chinese restaurant to eat black noodles (자장면 jajangmyeon) and “mourn” their single life.[50] Koreans also celebrate Pepero Day on November 11, when young couples give each other Pepero cookies. The date ’11/11′ is intended to resemble the long shape of the cookie. The 14th of every month marks a love-related day in Korea, although most of them are obscure. From January to December: Candle Day, Valentine’s Day, White Day, Black Day, Rose Day, Kiss Day, Silver Day, Green Day, Music Day, Wine Day, Movie Day, and Hug Day.[51] Korean women give a much higher amount of chocolate than Japanese women.[50]

In China, the common situation is the man gives chocolate, flowers or both to the woman that he loves. In Chinese, Valentine’s Day is called (simplified Chinese: 情人节; traditional Chinese: 情人節; pinyin: qíng rén jié). Traditional Chinese Valentine’s day is called “qixi” in pinyin, and is celebrated on the 7th day of the 7th month of the lunar calendar, commemorating a fabled day on which the cowherder and weaving maid are allowed to be together. Modern Valentines day is also celebrated on February 14 of the solar calendar each year.

In Republic of China (Taiwan) the situation is the reverse of Japan’s. Men give gifts to women in Valentine’s Day, and women return them in White Day.[50]

In the Philippines, Valentine’s Day is called “Araw ng mga Puso” or “Hearts Day”. It is usually marked by a steep increase in the prices of flowers.

Japan

In Japan, Morozoff Ltd. introduced the holiday for the first time in 1936, when it ran an advertisement aimed at foreigners. Later in 1953 it began promoting the giving of heart-shaped chocolates; other Japanese confectionery companies followed suit thereafter. In 1958 the Isetan department store ran a “Valentine sale”. Further campaigns during the 1960s popularized the custom.[52][53]

The custom that only women give chocolates to men appears to have originated from the typo of a chocolate-company executive during the initial campaigns.[54] In particular, office ladies give chocolate to their co-workers. Unlike western countries, gifts such as greeting cards,[54] candies, flowers, or dinner dates[50] are uncommon, and most of the activity about the gifts is about giving the right amount of chocolate to each person.[54] Japanese chocolate companies make half their annual sales during this time of the year.[54]

Many women feel obliged to give chocolates to all male co-workers, except when the 14th falls on a Sunday, a holiday. This is known as giri-choko (義理チョコ), from giri (“obligation”) and choko, (“chocolate”), with unpopular co-workers receiving only “ultra-obligatory” chō-giri choko cheap chocolate. This contrasts with honmei-choko (本命チョコ, Favorite chocolate); chocolate given to a loved one. Friends, especially girls, may exchange chocolate referred to as tomo-choko (友チョコ); from tomo meaning “friend”.[55]

In the 1980s the Japanese National Confectionery Industry Association launched a successful campaign to make March 14 a “reply day”, where men are expected to return the favour to those who gave them chocolates on Valentine’s Day, calling it White Day for the color of the chocolates being offered. A previous failed attempt to popularize this celebration had been done by a marshmallow manufacturer who wanted men to return marshmallows to women.[52][53]

Men are expected to return gifts that are at least two or three times more valuable than the gifts received in Valentine’s Day. Not returning the gift is perceived as the men placing himself in a position of superiority, even if excuses are given. Returning a present of equal value is considered as a way to say that you are cutting the relationship. Originally only chocolate was given, but now the gifts of jewelry, accessories, clothing and lingerie are usual. According to the official website of White Day, the color white was chosen because it’s the color of purity, evoking “pure, sweet teen love”, and because it’s also the color of sugar. The initial name was “Ai ni Kotaeru White Day” (Answer Love on White Day).[52][53]

In Japan, the romantic “date night” associated to Valentine’s Day is celebrated in Christmas Eve.[56]

In a 2006 survey of people between 10 and 49 years of age in Japan, Oricon Style found the 1986 Sayuri Kokushō single, Valentine Kiss, to be the most popular Valentine’s Day song, even though it sold only 317,000 copies.[57] The singles it beat in the ranking were number one selling Love Love Love from Dreams Come True (2,488,630 copies), Valentine’s Radio from Yumi Matsutoya (1,606,780 copies), Happy Happy Greeting from the Kinki Kids (608,790 copies). The final song in the top five was My Funny Valentine by Miles Davis.[57]

Similar Asian traditions

In Chinese culture, there is an older observance related to lovers, called “The Night of Sevens” (Chinese: 七夕; pinyin: Qi Xi). According to the legend, the Cowherd star and the Weaver Maid star are normally separated by the milky way (silvery river) but are allowed to meet by crossing it on the 7th day of the 7th month of the Chinese calendar.

In Japan, a slightly different version of 七夕 called Tanabata has been celebrated for centuries, on July 7 (Gregorian calendar).[58] It has been considered by Westerners as similar to St. Valentine’s Day,[59] but it’s not related to it, and its origins are completely different.

India

In India, in the antiquity, there was a tradition of adoring Kamadev, the lord of love; exemplificated by the erotic carvings in the Khajuraho Group of Monuments and by the writing of the Kamasutra treaty of lovemaking.[60] This tradition was lost around the Middle Ages, when Kamadev was no longer celebrated, and public displays of sexual affections became frowned upon.[60] Around 1992 Valentine’s Day started catching in India, with special TV and radio programs, and even love letter competitions.[60][61] The economic liberation also helped the Valentine card industry.[61]

In modern times, Hindu and Islamic[62] traditionalists consider the holiday to be cultural contamination from the West, result of the globalization in India.[60][61] Shiv Sena and the Sangh Parivar have asked their followers to shun the holiday and the “public admission of love” because of them being “alien to Indian culture”.[63] These protests are organized by political elites, but the protesters themselves are middle-class Hindu men who fear that the globalization will destroy the traditions in his society: arranged marriages, hindu joint families, full-time mothers (see Housewife#India), etc.[61][62]

Despite these obstacles, valentine’s day is becoming increasingly popular in India.[64]

However, leftist and liberal critiques of Valentine’s day remain strong in India. Valentine’s Day has been strongly criticized from a postcolonial perspective by intellectuals from the Indian left . The holiday is regarded as a front for Western imperialism, neocolonialism, and the exploitation of working classes through commercialism by multinational corporations.[65] Studies have shown that Valentine’s day promotes and exacerbates income inequality in India, and aids in the creation of a pseudo-westernized middle class. As a result, the working classes and rural poor become more disconnected socially, politically, and geographically from the hegemonic capitalist power structure. They also criticize mainstream media attacks on Indians opposed to valentine’s day as a form of demonization that is designed and derived to further the valentine’s day agenda.[66][67]

Middle East

In Egypt, Egyptians celebrate Valentine’s Day on February 14, and the indigenous Eid el-Hob el-Masri (Egyptian Love Day) on November 4, to buy gifts,and flowers for their lovers. It has been recorded on the February 14th, 2006 flower movement in the country, worth six million pounds, formed a gain of 10 per-cent of the total annual sale of flowers.

In Iran, the Sepandarmazgan, or Esfandegan, is an age-old traditional celebration of love, friendship and Earth. It has nothing in common with the Saint Valentine celebration, except for a superficial similarity in giving affection and gifts to loved ones, and its origins and motivations are completely unrelated. It has been progressively forgotten in favor of the Western celebration of Valentine’s Day. The Association of Iran’s Cultural and Natural Phenomena has been trying since 2006 to make Sepandarmazgan a national holiday on 17 February, in order to replace the Western holiday.[68]

In Israel, the Tu B’Av, is considered to be the Jewish Valentine’s Day following the ancient traditions of courtship on this day. Today, this is celebrated as a second holiday of love by secular people (besides Saint Valentine’s Day), and shares many of the customs associated with Saint Valentine’s Day in western societies.

Conflict with Islamic countries and political parties

Saudi Arabia

In Saudi Arabia, in 2002 and 2008, religious police banned the sale of all Valentine’s Day items, telling shop workers to remove any red items, as the day is considered a Christian holiday.[69][70] In 2008 this ban created a black market of roses and wrapping paper.[70]

Pakistan

The Jamaat-e-Islami political party has called for the banning of the holiday.[64] Despite this, the celebration is increasingly popular[64] and the florists expect to sell great amount of flowers, especially red roses.[71]

Iran

In the 21st century, the celebration of Valentine’s Day in Iran has been harshly criticized by conservatives who see the celebrations as opposed to Islamic culture. In 2011, the Iranian printing works owners’ union issued a directive banning the printing and distribution of any goods promoting the holiday, including cards, gifts and teddy bears. “Printing and producing any goods related to this day including posters, boxes and cards emblazoned with hearts or half-hearts, red roses and any activities promoting this day are banned… Outlets that violate this will be legally dealt with,” the union warned.[72][73]

See also

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to: Valentine’s Day |

- Antivalentinism

- Sailor’s Valentines

- Saint Valentine’s Day massacre

- Vinegar valentines

- Women’s Memorial March, held on Valentine’s Day in Vancouver, British Columbia.

References

- ^ a b The History of Valentine’s Day – History.com, A&E Television Networks. Retrieved February 2, 2010.

- ^ History of Valentine’s Day Christianity Today International. Retrieved February 2, 2010; “Then Again Maybe Don’t Be My Valentine”, Ted Olsen, 2000-01-02

- ^ a b HowStuffWorks “How Valentine’s Day works” – HowStuffWorks. Retrieved February 2, 2010.

- ^ a b Leigh Eric Schmidt, “The Fashioning of a Modern Holiday: St. Valentine’s Day, 1840–1870” Winterthur Portfolio 28.4 (Winter 1993), pp. 209–245.

- ^ Henry Ansgar Kelly, in Chaucer and the Cult of Saint Valentine (Leiden: Brill) 1986, accounts for these and further local Saints Valentine (Ch. 6 “The Genoese Saint Valentine and the observances of May”) in arguring that Chaucer had an established tradition in mind, and (pp 79ff) linking the Valentine in question to Valentine, first bishop of Genoa, the only Saint Valentine honoured with a feast in springtime, the season indicated by Chaucer. Valentine of Genoa was treated by Jacobus of Verazze in his Chronicle of Genoa (Kelly p. 85).

- ^ Oxford Dictionary of Saints, s.v. “Valentine”: “The Acts of both are unreliable, and the Bollandists assert that these two Valentines were in fact one and the same.”

- ^ “Valentine of Rome”. http://www.catholic-forum.com/saints/saintv06.htm. , catholic-forum.com

- ^ “Saint Valentine’s Day: Legend of the Saint”. novareinna.com. http://www.novareinna.com/festive/saintval.html.

- ^ “Valentine of Terni”. catholic-forum.com. http://www.catholic-forum.com/saints/saintv90.htm.

- ^ “Basilica of Saint Valentine in Terni”. virtualmuseum.ca. http://www.virtualmuseum.ca/Exhibitions/Valentin/English/6/622.php3.

- ^ “Catholic Encyclopedia: St. Valentine”. newadvent.org. http://www.newadvent.org/cathen/15254a.htm.

- ^ The present Roman Martyrology records, at February 14, “In Rome, on the Via Flaminia near the Milvian Bridge: St. Valentine, martyr.”

- ^ Calendarium Romanum ex Decreto Sacrosancti Œcumenici Concilii Vaticani II Instauratum Auctoritate Pauli PP. VI Promulgatum (Typis Polyglottis Vaticanis, MCMLXIX), p. 117

- ^ Legenda Aurea, “Saint Valentine”, catholic-forum.com.

- ^ a b “The History of Valentine’s Day”. History.com. http://www.history.com/minisite.do?content_type=Minisite_Generic&content_type_id=882&display_order=1&sub_display_order=1&mini_id=1084.

- ^ History of Valentine’s day, TheHolidaySpot.com

- ^ Jack B. Oruch, “St. Valentine, Chaucer, and Spring in February” Speculum 56.3 (July 1981:534–565)

- ^ Oruch, Jack B., “St. Valentine, Chaucer, and Spring in February,” Speculum, 56 (1981): 534–65. Oruch’s survey of the literature finds no association between Valentine and romance prior to Chaucer. He concludes that Chaucer is likely to be “the original mythmaker in this instance.” Colfa.utsa.edu

- ^ “Henry Ansgar Kelly, Valentine’s Day / UCLA Spotlight”. http://spotlight.ucla.edu/faculty/henry-kelly_valentine/.

- ^ “Chaucer: The Parliament of Fowls”. http://www.wsu.edu/~delahoyd/chaucer/PF.html. , wsu.edu

- ^ Kelly, Henry Ansgar, Chaucer and the Cult of Saint Valentine (Brill Academic Publishers, 1997), ISBN 90-04-07849-5. Kelly gives the saint’s day of the Genoese Valentine as May 3 and also claims that Richard’s engagement was announced on this day. Iol.co.za

- ^ Calendar of the Saints: 2 May, catholic-forum.com.

- ^ Oruch 1981:539.

- ^ Domestic Violence, Discourses of Romantic Love, and Complex Personhood in the Law – [1999] MULR 8; (1999) 23 Melbourne University Law Review 211

- ^ “Court of Love: Valentine’s Day, 1400”. http://www.virtualmuseum.ca/Exhibitions/Valentin/English/4/422.php3. , virtualmuseum.ca

- ^ A Farewell to Love in wikisource

- ^ History Channel, historychannel.com.

- ^ Spenser, The Faery Queene iii, Canto 6, Stanza 6: on-line text

- ^ Gammer Gurton’s Garland (London, 1784) in I. Opie and P. Opie, The Oxford Dictionary of Nursery Rhymes (Oxford University Press, 1951, 2nd edn., 1997), p. 375.

- ^ Ummah.net

- ^ Emotionscards.com

- ^ “Valentine’s Day worth £1.3 Billion to UK Retailers”. British Retail Consortium. http://www.brc.org.uk/details04.asp?id=1091&kCat=&kData=1.

- ^ Schmidt 1993:209–245.

- ^ Quoted in Schmidt 1993:209.

- ^ a b c “Americans Valentine’s Day”. U.S. Greeting Card Association. 2010. http://www.greetingcard.org/userfiles/file/2010%20Valentines%20Day.pdf. Retrieved 2010-02-16. [dead link]

- ^ a b Eve Devereux (2006). Love & Romance Facts, Figures & Fun (illustrated ed.). AAPPL. p. 28. ISBN 1904332331. http://books.google.com/?id=MCAC8mnwEIEC

- ^ Hobbies, Volume 52, Issues 7–12 p.18. Lightner Pub. Co., 1947

- ^ a b Emotionscards.com Esther Howland

- ^ Dean, Dorothy (1990) On the Collectible Trail p.90. Discovery Publications, 1990

- ^ Gaskell, Elizabeth Cranford and Selected Short Stories p.258. Wordsworth Editions, 2006

- ^ Leigh Eric Schmidt, “The Commercialization of the calendar: American holidays and the culture of consumption, 1870–1930” Journal of American History 78.3 (December 1991) pp 890–98.

- ^ Valentine`s Day versus Dragobete, cultura.ro (Romanian)

- ^ Notimex. “Realizará GDF cuarta feria por Día del Amor y la Amistad”. milenio.com. http://www.milenio.com/node/380160.

- ^ Alexander Sanchez C. (2010-02-12). “El cine transpiraamores y desamores”. La Nación (La Nación (San José)). http://www.nacion.com/viva/2010/febrero/12/tiempolibre2234449.html

- ^ “Sacoto canta por San Valentín”. El Comercio. http://ww1.elcomercio.com/noticiaEC.asp?id_noticia=334553&id_seccion=7. “El cantante y compositor presentará un show romántico por el Día del Amor y la Amistad.” [dead link]

- ^ “Para quererte”. El Periódico de Guatemala. 2010-02-10. http://www.elperiodico.com.gt/es/20100210/opinion/137067/

- ^ The Psychology of Carnaval, TIME Magazine, February 14, 1969

- ^ Video of Chavez joking about Valentine’s day, youtube.com, 2009-01-31

- ^ Domingo, Ronnel. Among Asians, Filipinos dig Valentine’s Day the most. Philippine Daily Inquirer, February 14, 2008. Retrieved 21 February 2008.

- ^ a b c d Risa Yoshimura (2006-02-14). “No matter where you’re from, Valentine’s Day still means the same”. The Pacer. http://pacer.utm.edu/2926.htm

- ^ Korea rivals U.S. in romantic holidays[dead link], Centre Daily Times, February 14, 2009.

- ^ a b c Gordenker, A. “So, what the heck is that? White Day”. in Japan Times. (March 21, 2006).. Retrieved June 30, 2007.

- ^ a b c Katherine Rupp (2003). Gift-giving in Japan: cash, connections, cosmologies (illustrated ed.). Stanford University Press. pp. 149–151. ISBN 0804747040. http://books.google.com/?id=KHkyUp-EH2MC&lpg=PA150&dq=japan%20valentine’s%20day&pg=PA145#v=onepage&q=japan%20valentine’s%20day

- ^ a b c d Chris Yeager (2009-02-13). Valentine’s Day in Japan. Japan America Society of Greater Philadelphia (JASGP). http://jasgp.org/content/view/636/179/

- ^ Yuko Ogasawara (1998). University of California Press. ed. Office Ladies and Salaried Men: Power, Gender, and Work in Japanese Companies (illustrated ed.). Berkeley: University of California Press. pp. 98–113, 142–154, 156, 163. ISBN 0520210441. http://books.google.com/?id=9_yjfAZo4jIC&pg=PA98&vq=valentine+day&dq=japan+chocolate+saint+valentin.

- ^ Ron Huza (he was an ESL in Japan for 11 years) (2007-02-14). “Lost in translation: The cultural divide over Valentine’s Day”. The Gazette. http://www.canada.com/montrealgazette/news/editorial/story.html?id=2ae6a44a-2f29-45a3-a257-2a13b3d3149d

- ^ a b “大公開!『バレンタインソング』といえばこの曲! [The Great Exhibition! When speaking of a “Valentine song”, this is the song!]” (in Japanese). Oricon Style. February 3, 2006. Archived from the original on March 17, 2010. http://www.webcitation.org/5oIA3Hpll. Retrieved March 17, 2010.

- ^ Caprice Reflections AuthorHouse, 2007

- ^ E.I.S. (1925-02-15). “Japan has a Valentine Day based on a tender legend”. New York Times. http://select.nytimes.com/gst/abstract.html?res=F20612FD395B12738DDDAC0994DA405B858EF1D3

- ^ a b c d “India’s fascination with Valentine’s Day. The BBC’s Vijay Rana explains how Valentine’s Day has replaced more traditional celebrations of love in India”, BBC, 14 February 2002, http://news.bbc.co.uk/2/hi/south_asia/1820440.stm

- ^ a b c d Steve Derné (2008), “7. Globalizing gender culture. Transnational cultural flows and the intensification of male dominance in India”, in Kathy E. Ferguson, Monique Mironesco, Gender and globalization in Asia and the Pacific: method, practice, theory, University of Hawaii Press, pp. 127–129, ISBN 0824832418, 9780824832414, http://books.google.com/books?id=60o6NLFlbhoC

- ^ a b George Monger (2004), Marriage customs of the world: from henna to honeymoons (illustrated ed.), ABC-CLIO, ISBN 1576079872, 9781576079874, http://books.google.es/books?id=o8JlWxBYs40C

- ^ Anil Mathew Varughese (2003), “Globalization versus cultural authenticity? Valentine’s Day and Hindu values”, in Richard Sandbrook, Civilizing globalization: a survival guide, SUNY series in radical social and political theory (illustrated ed.), SUNY Press, p. 53, ISBN 0791456676, 9780791456675, http://books.google.es/books?id=XSZD-bpo3S8C

- ^ a b c Hindu and Muslim anger at Valentine’s. BBC. 2003-02-11. http://news.bbc.co.uk/2/hi/south_asia/2749667.stm

- ^ Sharma, Satya. “The cultural costs of a globalized economy for India”. Dialectical Anthropology 21 (3-4): 299–316. doi:10.1007/BF00245771.

- ^ Mankekar, Purnima (1999). Screening, Culture, Viewing Politics: An Ethnography of Television, Womanhood Nation in Postcolonial India. Duke University Press.

- ^ As quoted in ‘India Today: Pot Pourri Generation’ 15th September issue, 2005

- ^ Esfandegan to Replace Valentine. Iran Daily. 2008-12-31. p. 6. http://www.nitc.co.ir/iran-daily/1387/3307/pdf/i6.pdf , nitc.co.ir

- ^ “Cooling the ardour of Valentine’s Day”. BBC News. 3 February 2002. http://news.bbc.co.uk/2/hi/middle_east/1818642.stm.

- ^ a b “Saudis clamp down on valentines”. BBC News. 11 February 2008. http://news.bbc.co.uk/2/hi/middle_east/7239005.stm.

- ^ Flower sellers await Valentine’s Day. The Nation. 2010-02-08. http://www.nation.com.pk/pakistan-news-newspaper-daily-english-online/Regional/Islamabad/08-Feb-2010/Flower-sellers-await-Valentines-Day

- ^ Iran shops banned from selling Valentine gifts, AFP 02-01-2010

- ^ Iran snubs Valentine’s Day, AP (published in The Washington Post) 02-01-2010

- Wikipedia